A summary of the RUSI paper with commentary:

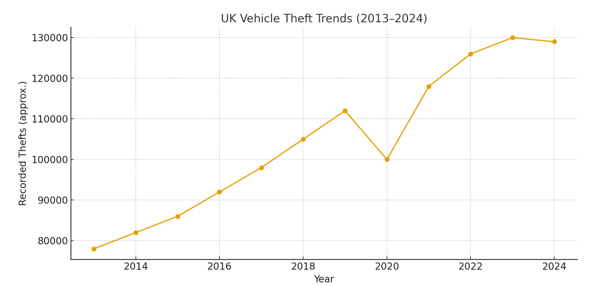

Vehicle Theft Statistics

- Vehicle thefts in the UK increased by 75% since 2013–14, reaching 136,396 in 2022–23 (p.2).

- In England and Wales, 129,127 incidents were recorded in 2023–24 (p.2).

- Theft rates rose from 2.71 to 4.42 per 1,000 cars between 2014–2023 (p.2).

- Scotland: steady at ~5,000 annually since 2015 (p.2).

- Northern Ireland: decline from 2,066 (2011–12) to 995 (2023–24), >50% fall (p.2).

NOTE:

‘vehicle’ is a broad description, encompassing anything from a quad bike to HGV. Figures are many, varied and unreliable.

Recovery Rates

- References to recoveries appear in the context of NaVCIS and police “intensification weeks” (p.12, n.34).

- No systematic national recovery rate is provided.

- Enforcement often focuses on quick recoveries rather than disrupting networks (p.22).

NOTE:

The report does not provide national statistics on the proportion of vehicles recovered vs. permanently lost.

NaVCIS records are less likely to involve a vehicle taken by ‘theft‘ i.e. stolen. They will more commonly, if not exclusively, relate to vehicles taken by ‘fraud‘.

Recovery rates are misleading – not defined, and cover a multitude.

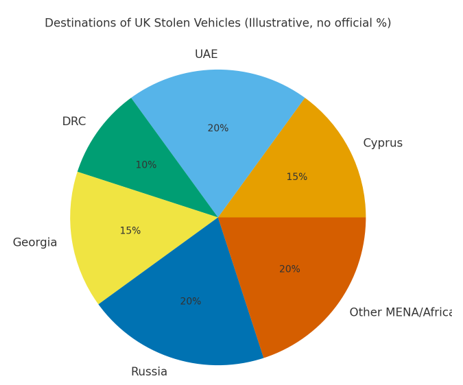

Destinations for Stolen Vehicles

- Vehicles are frequently exported within 24 hours via ports such as Dover (p.8).

- Destinations identified: Cyprus, UAE, Democratic Republic of Congo, Georgia, Central Asia, Middle East, North/West Africa, Russia (pp.8, 14–15).

- High-value UK vehicles reappear in Moscow despite sanctions (p.15).

- Chop shops also distribute parts internationally (p.10).

NOTE:

‘exported within 24 hours’ appears to be at odds with stealing and leaving to determine whether a tracker is fitted.

Little destination data appears to be available.

Once they have left the country, there appears to be little appetite to repatriate stolen vehicles.

Condition of Vehicles Recovered

- Vehicles are often stripped for parts in chop shops, sometimes fitted dangerously into rebuilt cars (p.13).

- Parts resold online, including via eBay, and are sometimes fitted into vehicles deemed unsafe to drive (p.13).

NOTE:

No statistics are provided for recovered vehicle conditions (e.g., intact, stripped, burnt out).

Keyless Stealing / Security Bypass

- Relay attacks and CAN bus injection were identified as primary methods (pp.7–8, 16–17).

- Devices cost up to £20,000, some disguised as consumer electronics (p.7).

- Rapid “arms race” between criminals and manufacturers (pp.16–17).

NOTE:

Why ‘security bypass’ theft activity is considered a ‘primary’ method is unknown. It is a questionable conclusion, seemingly at best a hypothesis.

Is an ‘arms race’ ultimately the solution? After all, ‘no car is theft proof‘.

Supporting Evidence of Keyless Theft

- Cited technical reports explain CAN bus injection (p.7).

- Industry interviews confirm rapid spread, cheaper “knock-offs” and online tutorials (pp.7–8).

- Evidence that organised crime invests in R&D, not opportunistic crime (p.7).

NOTES:

The evidence in support of the extent of keyless taking is unknown.

NaVCIS (mentioned above) vehicles are likely taken with keys due to the nature of the ‘taking’, which is by fraud (deception), not by theft.

Suggested Solutions / Countermeasures

- Recommendations (pp.23–26):

- Promote proactive manufacturer security measures.

- Fill intelligence gaps (ports, illicit finance, tech like AI/3D printing).

- Explore new funding models (e.g. surcharge on insurance, Canadian ATPA model).

- Establish a national coordination body for vehicle theft.

- Ban on sale/possession of theft devices proposed under Crime and Policing Bill 2025* (p.18).

NOTE:

Security improvements may delay taking, may require criminals to evolve, adapt.

Partnerships are required and should extend beyond ‘a select few’ – understanding the environment, adopting lawful DPA practices and sharing should occur.

Do we need yet another ‘national coordination body’, and if so, why, what gaps will it fill?

Why do current laws fail- or is there a reluctance or inability to utilise current legislation?

Fraudulent Reports of Vehicle Taking

- The report discusses fraud in vehicle acquisition (false IDs, leases, cloned documentation) (pp.9–11).

- It does not address false insurance claims or fraudulent reports of theft by owners.

NOTE:

Untrue theft reports skew figures. False allegations are likely significant in number and will impact upon investigations, prosecutions and recovery (statistics).

A change in approach to vehicle crime needs to start from the initial notification.

Police officers need to understand the basics of vehicle theft and vehicle investigation. This expertise appears to have faded away with the specialist Stolen Vehicle Squads (SVS) – a further indication of the crime being devalued, considered low priority.

Theft vs. Fraud Distinction

- Fraudulent leases/finance scams are described as an OCG typology (p.9).

- Stolen-to-order vs. fraudulent acquisition is clearly differentiated in typologies (pp.9–11).

NOTE:

Statistical data does not distinguish vehicle taking by THEFT from vehicle taking by FRAUD offences. The methodologies are very different. In turn, concerning vehicles taken by FRAUD, consideration should be given to:

- The treatment of an innocent purchaser found in possession of a vehicle

- Whether the title in the vehicle was passed to the innocent purchaser

Suggested Further Considerations:

- Recovery rates: No national statistics – vital for understanding law enforcement effectiveness.

- Condition of recovered vehicles: No data – important for measuring impact on victims/insurance.

- Fraudulent theft reports: Not addressed – misses potential insurance fraud dimension.

- Leadership/brokers in OCGs: Little info’ on high-level organisers (p.11).

- Commercial vehicles: Limited coverage, though theft is significant for businesses.

The following summarises the key findings of the RUSI paper ‘Organised Vehicle Theft in the UK: Trends and Challenges’ (June 2025).

UK Vehicle Theft Timeline (2013–2024)

This chart illustrates the approximate trend of vehicle thefts across the UK between 2013–2024, based on figures referenced in the RUSI report.

Destinations of UK Stolen Vehicles

Illustrative distribution of key foreign destinations for stolen UK vehicles (Cyprus, UAE, DRC, Georgia, Russia, MENA/Africa). Percentages are indicative only, as the report does not provide systematic data.

Title Considerations

Whether title to stolen property can be acquired in other countries may impact their disclosure of information and/or the merit of being advised of a recovery (and in turn pursuing repatriation). Enquiries of the above destination countries are limited by open‐source availability and language/translation barriers. Regarding whether an innocent purchaser of a stolen vehicle can gain title, the relevant legislation, legal complexities, and illustrative cases or commentary are as below.

That no clear source could be found is likely an indicator of risk and ambiguity. Whilst the Interpol website carried information, it appears this has been removed. Historical Interpol information, which may be relevant country by country, can be found here.

Key Legal Principle & Caveats (General Background)

In many common law jurisdictions, there is a doctrine that ‘nemo dat quod non habet‘ (one cannot give what one does not have). In basic terms, if the seller does not have good title (because the vehicle was stolen), an innocent purchaser usually cannot acquire good title merely by purchase. That said, some jurisdictions introduce exceptions or statutory protections (e.g. good faith purchaser, registration systems, statutory assurances) which complicate pure nemo dat.

Legal regimes differ greatly in civil vs. common law systems; the existence of vehicle registration systems, title registries, anti-fraud checks, and the strength of the courts are all relevant.

In cross-border theft, the interplay of local law, international cooperation, mutual legal assistance, treaties, and ownership claims becomes critical. The fact that a vehicle is stolen in the UK and brought to another country will often require litigation in that country, or formal repatriation processes, which may be weak or non‐existent.

Many of the countries identified in the RUSI report are not primarily English‐law systems, so one must look to local legislation or civil/mixed legal codes.

NOTE:

‘Theft’ and ‘Fraud‘ can be improperly used synonymously, confusingly. In some jurisdictions, whilst title cannot pass in property obtained by THEFT, title may pass if the property was obtained by FRAUD.

The Schengen Convention no longer applies post-Brexit.

There appears to be little appetite by UK law enforcement to pursue vehicles located abroad.

Below is a summary of information located online.

Cyprus

Legal System & Title Regime

Cyprus follows a mixed legal system influenced by common law and civil law. Immovable (real property) law in Cyprus is fairly well documented, but vehicle/title law is less publicly exposed in English sources.

Available Indicators & Commentary

A forum commentary (not authoritative) claims: “If you purchase property in good faith … and it is later found to be stolen then there is a procedure … In some cases the new owner … keeps the property whilst the old owner … is considered more able to survive the loss.” (cyprus44.com)

But this is anecdotal and not a reliable statement of Cyprus vehicle law.

Historical Interpol information can be read here.

Risk & Ambiguity

In the absence of clear statutory or case evidence, Cyprus should be considered a jurisdiction with uncertain or high-risk title environment for stolen vehicles.

An innocent purchaser in Cyprus who bought a vehicle later determined to be stolen may well face legal challenge, with the original (UK) owner or insurers potentially bringing a claim to recover the vehicle, depending on bilateral legal cooperation, mutual assistance, and the willingness of courts to enforce foreign judgments.

Lack of transparency in vehicle registration records and possible weak enforcement could further complicate matters.

United Arab Emirates (UAE)

Legal System & Vehicle Title Regime

The UAE is a civil law / Islamic law influenced jurisdiction, with a combination of federal and emirate-level regulation.

Vehicle registration and licensing in UAE is handled by each emirate’s traffic authority (e.g. RTA in Dubai).

Historical Interpol information can be read here.

Title & Innocent Purchaser Risk

No clear source was located confirming that an innocent purchaser can acquire title to a stolen vehicle in the UAE.

Given the general legal principles, it is likely that if a vehicle is proved stolen, ownership claims would override a later purchaser’s rights, unless the purchaser had some specific legal protection – no reference was located to this.

The requirement for vehicle registration, insurance, and checking records before sale may present some practical safeguards for a purchaser.

Illustrative Legislative or Regulatory Notes

Vehicle insurance in UAE is mandatory.

Risk & Practical Realities

In practice, cross-emirate and cross-country enforcement, and the capacity of authorities to detect and reverse fraudulent registrations, will matter.

If someone buys a vehicle that turned out to be stolen, the traffic authority or courts might seize it, or the original owner (or UK authorities) might request repatriation.

Georgia (country, not U.S. state) / Russia / Eastern Europe (and analogous jurisdictions)

Some potentially relevant information:

Russia / CIS Countries (General Notes)

Many post-Soviet legal systems follow civil law traditions with registration of vehicles. Title is often tied to registration, but registration fraud, forged documents, and weak enforcement are apparently common issues.

In Russia, ownership is recorded in state vehicle registers (ГАИ, МВД), and a registration certificate and ownership documents are key.

The risk is high that the original owner’s claim would dominate, especially if export fraud, import checks, or legal cooperation exists.

Historical Interpol information can be read here.

Georgia (the country)

Unable to locate a reliable English legal source describing a Georgia statute on stolen vehicle title or registration regime, the risk is that a subsequent purchaser does not gain title, especially in cross-border theft cases.

Historical Interpol information can be read here.

Summary Table & Observations

| Jurisdiction | Legal System | Evidence of Innocent Purchaser Acquiring Title | Legislation / Registers | Complexity & Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyprus | Mixed (common + civil) | No clear authoritative evidence for vehicles | Immovable property laws exist; vehicle laws opaque | High risk; legal claims might prevail over purchaser |

| UAE | Civil / Islamic / federal structure | No clear evidence | Vehicle registration by emirate traffic authorities, mandatory insurance | Likely original owner claim would dominate |

| Georgia / Russia / CIS | Civil law / post-Soviet | No reliable source found | Vehicle registers exist, but enforcement weak | High risk; legal claims likely prevail |

For the main destination jurisdictions identified in the RUSI report (Cyprus, UAE, Georgia, Russia, parts of Africa), there is no readily accessible, authoritative open-source proof that an innocent purchaser can safely acquire title to a vehicle stolen from the UK.

The legal systems are likely to favour the original owner (or insurers) upon proof of theft, particularly where police, customs, or courts cooperate internationally.

The cross-border nature of the theft complicates everything: even if local courts are friendly, enforcement of judgments, cooperation with UK or EU authorities, and the existence of mutual legal assistance treaties matter.

For further information – ‘repatriation‘.